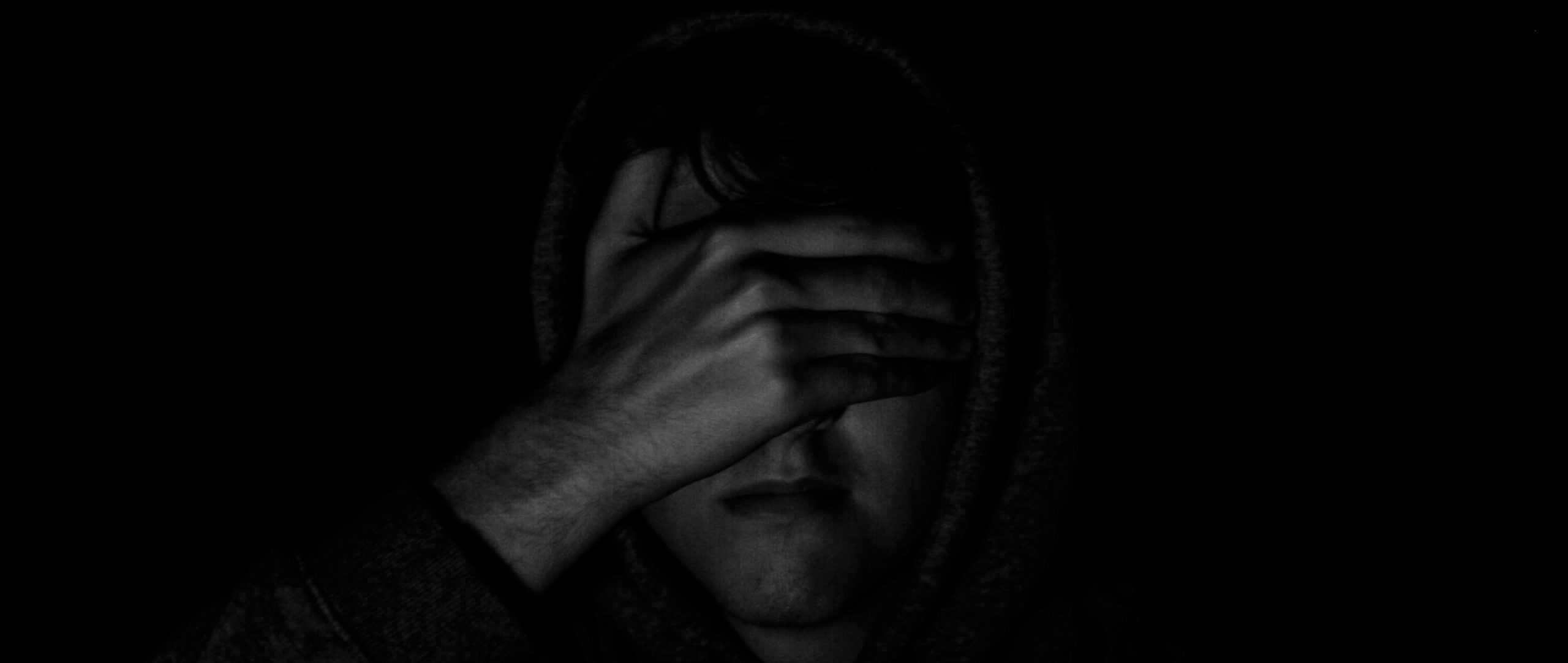

Watching people’s shoes as they walked, Goni had become an expert in knowing who would stop to put some money in his bowl. He couldn’t look them in the eye. Even the briefest human connection was unthinkable for him, but some passers-by would see his pathetic form on the pavement, and some would leave him some coins. So Goni stared at the pavement living what he calls his “black and life”.

After countless hours it would be time to buy something to eat. As night came Goni wondered if he would be spared the attention of the drug addicts who roamed the streets of Tirana looking for money to fuel their habits. He had grown used to the beatings and losing what little money he had left. Just another part of life on the streets. In the summer he could avoid the more organised criminal gangs. During the winter they knew where to find young homeless people, who would then be pressed into service as drug-couriers. It was dangerous work, but you couldn’t refuse it. At least they’d probably provide him with somewhere to sleep. Probably.

All this was normal for Goni. What was not normal was the severe infection in his lungs that was making breathing more and more difficult, and the scabies that was adding another level of misery. Four continuous years on the street had taken their toll. Goni was very afraid that this winter would be his last.

It was in this condition that two French missionaries found Goni one December. They took him to hospital and made sure he was taken care of. They also suggested he apply to join the House of Opportunity in Elbasan. They’d asked Goni whether he’d like the chance to get off the streets two years previously, but he thought that the House of Opportunity would be just another institution, like the orphanages he spent his childhood running away from. He hated the orphanages. He’d refused even to consider it back then. Now, with his health and strength ebbing away, and looking at the real possibility of dying at 22, Goni jumped at the chance. Right now, a safe place to sleep and somewhere to rest when he got out of hospital was as much as he could hope for. He would leave when the time was right.

So it was that after his stay in hospital, Goni joined the House of Opportunity.

To Goni’s surprise the House was nothing like he expected. He’d imagined a large, cold building, staffed by uncaring workers. The warm reception he received and welcoming home that he entered was something new. The people in charge were friendly, so were the young residents. They seemed to care, and they were telling him that he had a chance to make some big changes to his life. They said they would support him. Despite all this, Goni was suspicious. Sure, he had heard about regular families. They were outside of his experience though. Was this what they were like? He made sure nobody got too close. Shouting abuse, avoiding eye contact, making accusations – the distancing tactics he’d employed in the orphanages came in use again.

What was not surprising was the voice in Goni’s head telling him to leave. This is too hard. Go back to what you know. He begged on the streets of Elbasan a few times. It was easier looking at shoes on the pavement than looking the House of Opportunity team and his housemates in the eye.

Goni didn’t have a family, but he did have a mother, and she had set the pattern for his life. Until he was four, Goni’s mother had used him to help her beg on the streets. By the time he was scooped up by social services and taken into state care, Goni had grown used to staring at that pavement, and living a wretched existence. Goni grew more resentful as he was labelled a beggar, and a person of no value from the moment he entered the orphanage. So, he fought all the following fourteen years to escape from the orphanages that he was switched between. He made life difficult for everybody around him, and often absconded to go back on the streets of whatever city he was in at the time. When he reached 18, Goni returned to the streets without any worries that he would be dragged back to the orphanage. He was free to live life as he chose.

Goni couldn’t get rid of the idea of leaving the House of Opportunity. Come the late summer, when his mother got back in touch, Goni did just that. She could always draw him back. Back to the streets of Tirana, back to his black and white life. There was a strange comfort in the familiar here, at least.

After a few months the comfort of the streets began to fade. Goni realised something. He missed the House of Opportunity. He missed the people. He even missed the eye contact. He definitely missed being treated as a man, with respect. He missed having a horizon that didn’t include the closest pair of shoes. He understood now that there was no future for him on these streets, no dignity to be found in this life.

Dignity. Something else he had been treated with at the House of Opportunity. Goni compared his few brief months in the House to his life on the streets. He found the streets wanting. With a wrench he pulled away from his mother and headed back to Elbasan and sought the help he needed. He pleaded with the team, “This is a very bad addiction that I have created from begging, but I find it very difficult to get away from her! Please help me”.

We would so love to be able to share that Goni returned to the House of Opportunity and is now making a success of life. For nearly four months, it seemed like he might. But one day, Goni gave in to the call of his mother and the streets and left the House again.

The team think about him constantly, wondering how and where he is. Goni would be welcomed back, should he finally want to break the hold that his “black & white” life has on him. It wouldn’t be the first time that a traumatised young person took several attempts before finally committing to the process and making the change. We just hope Goni is the next.

You can donate to help those vulnerable young people that do make their break, here. The House of Opportunity in Elbasan is run by our partners, A2B Albania.